by Lynn Barendsen

As we think about what’s involved in carrying out good work and the challenges we face in our efforts, whether or not we realize it, issues of responsibility are often at the core of our decision-making. Some examples:

Should I stick to my principles and speak up in a group meeting or go along with a majority that feels otherwise?

Should I confront my colleague about hurtful actions or remain quiet in an effort to keep the peace?

Should I tell the truth or remain quiet to protect someone close to me?

In the mid 1990s, when we began our research into what eventually became a study of good work, we interviewed well over a thousand workers in a variety of different domains. One of the most revealing questions we asked was “to whom or what do you feel responsible in your work?” Using this question as a reflection prompt for students and for educators, we have been struck by the impact of this simple inquiry. One student, having written a long list of his responsibilities, said “no wonder I’m so stressed!” Of course, simply making a list of responsibilities doesn’t mean that choices between them are spontaneously clear or obvious. But the process does help to reveal the factors that pull us in various directions, and sometimes this additional information can aid in decision-making.

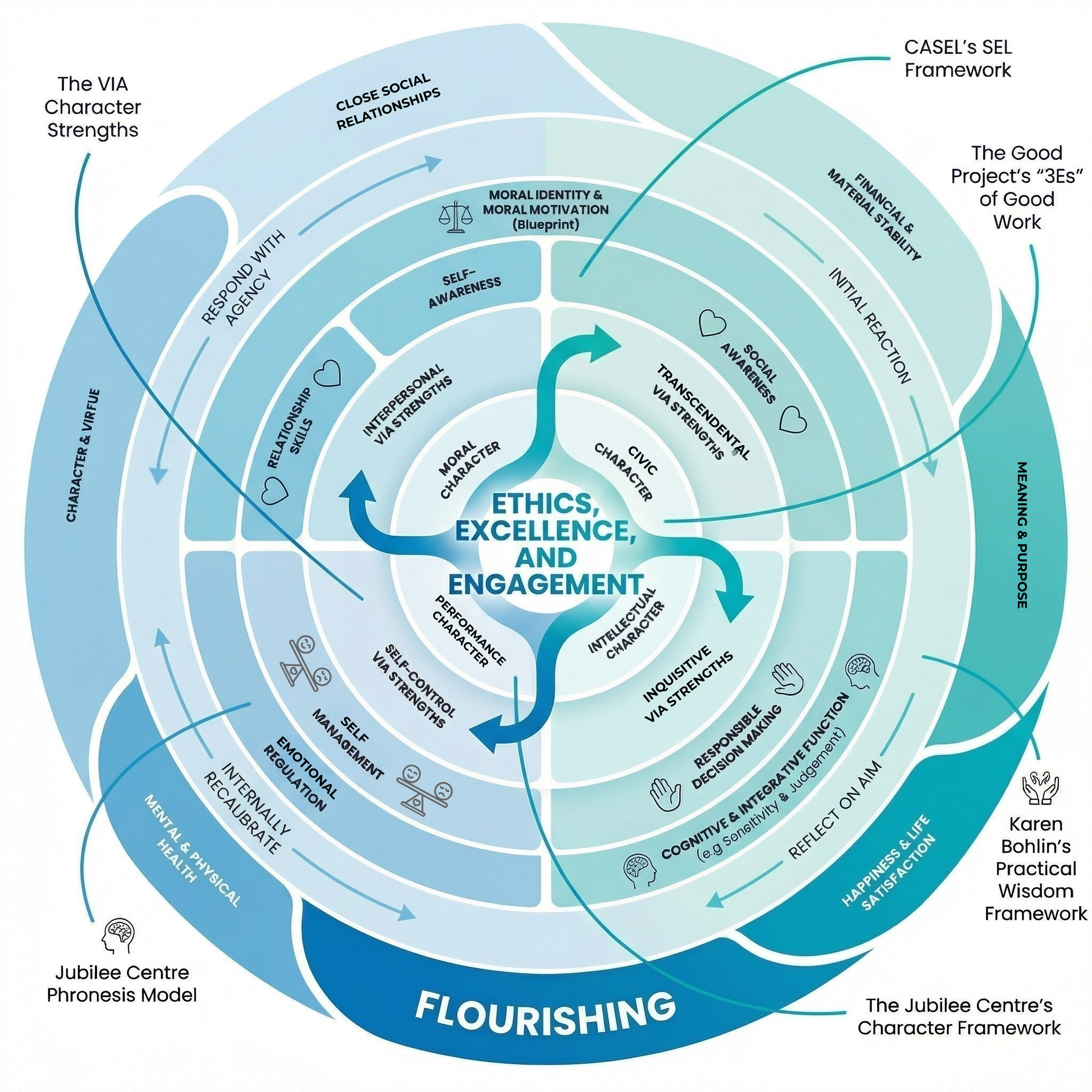

When we grapple with ethical dilemmas, we are often wrestling with conflicting responsibilities: responsibilities to ourselves, to our friends, to our families, to our co-workers, our workplace or profession, or to the wider world. Some of us express a sense of responsibility to our religion, to our identity or identities, to principles or ideals. Responsibility is a core idea on The Good Project for many reasons: how we understand our responsibilities (and which responsibilities take priority) is closely related to what we value and, which of those values have priority, how we construe our roles in the world, and what we understand our identities to be. Taking ownership for our work and its impact on the world is key to our understanding of what it means to do good work.

Over the years, we have written a great deal on the topic of responsibility. In fact, we’ve written an entire book on the topic, where various authors examine different aspects of responsibility through the lens of “good work” and additional perspectives: i.e., the relationship between creativity and responsibility, how responsibility may be understood differently by various groups (genders, types of workers, individuals who are/are not religious), considering responsibility as an “ability” to be responsive.

In the world of education, teachers juggle multiple responsibilities, and during these past few years, many have felt overburdened by them. Although many tell us they feel their primary responsibility is to their students, they are conflicted about how best to fulfill these obligations. Some examples of dilemmas in which teachers struggle with responsibility might be found here (links in titles):

The Protest: A teacher struggles to decide whether to take a stance about an issue she believes in (responsibility to ideal) or to respect another’s privacy (responsibility to colleague).

Discriminating Decisions: An educator is deeply conflicted about following directions at work when the request conflicts with her core beliefs (responsibility to workplace versus responsibility to an ideal).

The Meaning of Grades: A professor grapples between his responsibility to his beliefs (learning for learning’s sake) versus responsibility to his students (opportunities that might be lost if their grades aren’t top notch).

Looking Good: The issue of grade inflation is explored from a slightly different angle as a teacher in a new pilot school is torn between his responsibilities to his students and to the school itself.

Excellence at Risk: A teacher’s safety is at risk when a student threatens her, and she is torn about whether or not to press charges (responsibilities to self, to student, to the community).

We offer a number of additional resources on our website that address responsibility in various ways:

This video describes the research findings that led to the development of the Circles of Responsibility.

These writing prompts which encourage reflection about our various obligations and decision-making.

This video, in which the GP team uses the idea of responsibility to unpack and analyze an ethical dilemma from our dilemmas database.

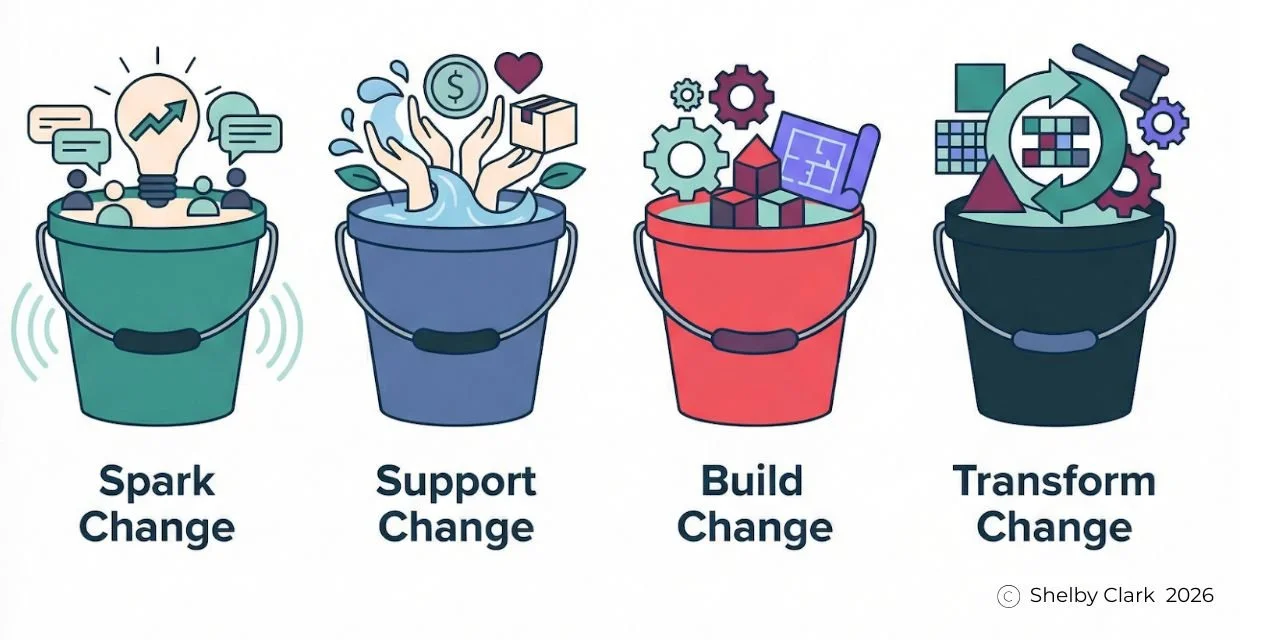

Several blogs tackle the topic of responsibility from varied angles. Howard Gardner uses the rings of responsibility in this blog to analyze the life and work of John F. Kennedy. Two blogs consider responsibility in light of the COVID pandemic: Shelby Clark writes about encouraging student responsibility during the pandemic here; in this blog, Kirsten McHugh uses the rings of responsibility as a tool to reflect on how understandings of personal and professional responsibilities since the beginning of the pandemic.

Revisiting responsibilities regularly can be a useful exercise, especially as most of us are regularly juggling multiple obligations. Taking the time to pause, reflect and consider our responsibilities (perhaps using the 5 Ds as a guide) may help to identify core values driving our work.