5 Ds, 3 Es and One Good Citizen

by The Good Project Team

Given recent events in the United States—increasing political division, yawning inequality between the country’s richest and poorest inhabitants, and well-documented violence directed towards people of color—the need for “good citizens'' is compelling. And that’s just within our borders. We need to attend as well to worldwide issues such as climate change and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Everyone is now a global citizen as well.

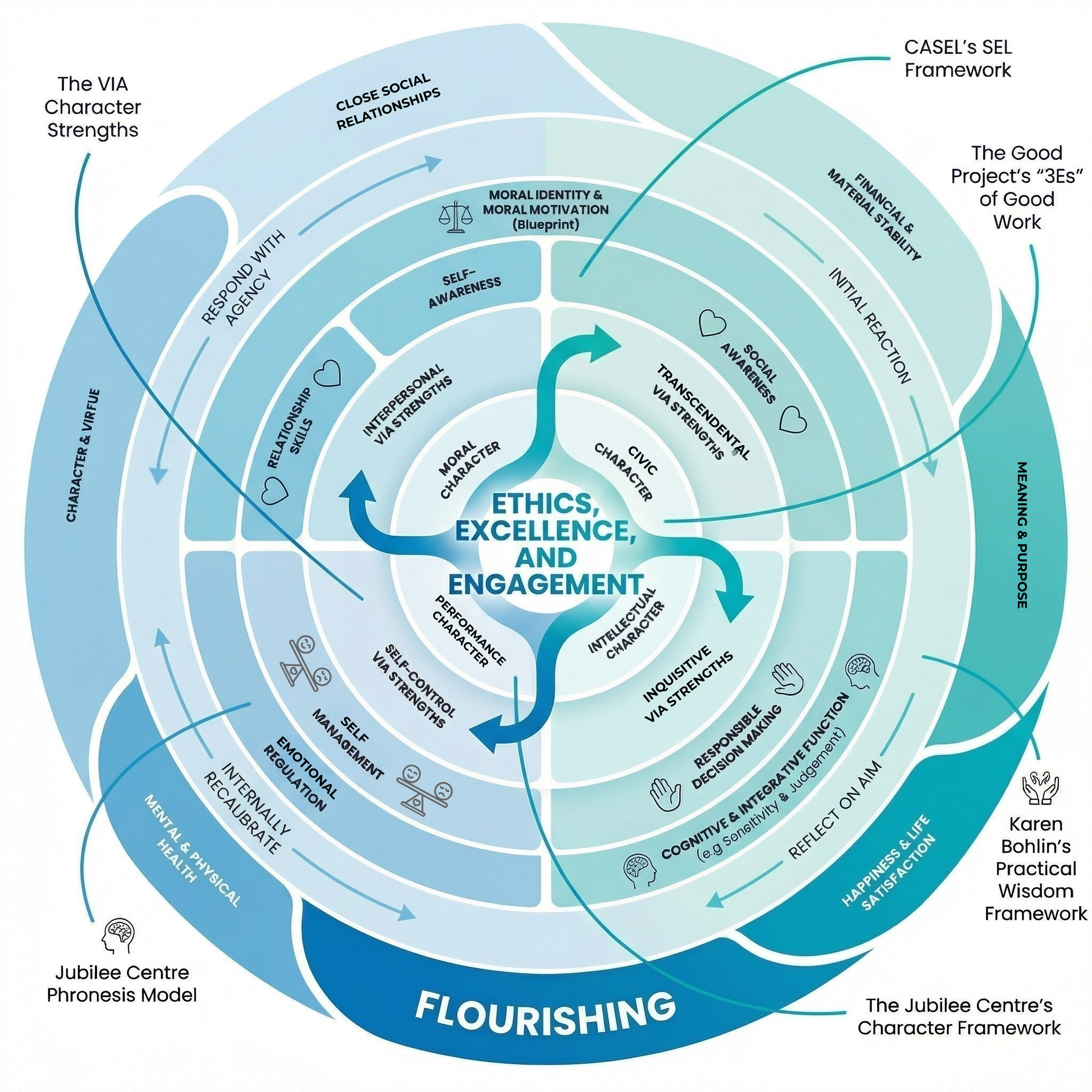

Our overarching goal at The Good Project is to help foster moral and ethical reflection in students and adults. One promising means of doing so is to practice reflecting on real-life dilemmas as they are encountered. In our conception, such reflection optimally draws on “Five Ds”:

Defining the dilemma one is faced with;

Discussing the dilemma with others;

Debating the pros and cons of various courses of action;

Deciding on an action (or deciding not to act); and

Debriefing the dilemma by reflecting on what went right, wrong, or what might be done better next time one encounters a similar situation.

Let us take each of these in turn.

Defining the Dilemma

In our work on dilemmas, we speak about times when people are not sure about the “right course of action” or feel torn between conflicting responsibilities. To date, we’ve compiled fifty dilemmas in our online dilemmas database; these can be drawn on in discussions on all sorts of topics, across the range of ages, demographies, and fields of endeavor.

As just one example, let’s use our dilemma “Divided Loyalties.”

Sara is the executive director of a national nonprofit that represents the concerns of America’s independent workforce, including freelancers, consultants, part-timers, and the self-employed. Sara’s grandfather was vice president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and although she never met her grandfather, she has been very much influenced by his work as a union organizer.

Soon after being recognized as one of a group of outstanding social entrepreneurs, Sara was invited to the World Economic Forum (WEF), a meeting of leaders of governments and corporations from around the world. Because the WEF gathers so many powerful individuals together, there are often protests of one form or another, and Sara would have been forced to cross a picket line in order to attend the WEF. In this case, she felt torn between a loyalty to her roots in the labor movement and a responsibility to her role as a noted social entrepreneur.

Clearly Sara feels a dilemma. One way to clarify that dilemma is to say that she is torn between her sense of neighborlly morality and the ethics of her role. Neighborly morality refers the ways in which individual treats those in their immediate social circles; it includes behaviors such as honesty, kindness, caring, attentiveness, and other prosocial behaviors. In contrast, ethics of roles refers to the standards, norms, and regulations expected of those acting in a professional capacity (including students); one might think of the Hippocratic Oath for those in the medical field or the ethics expected of a journalist, a lawyer, a teacher, an auditor..

In Sara’s case, she is being asked to adhere to the ethics of her role as a social entrepreneur—to advance the causes that she espouses in a responsible way. On the other hand, feelings of neighborly morality might call for her to show respect to those on the picket line—especially given her strong feelings of familial loyalty.

Discussing and Debating the Dilemma

How should Sara decide what to do? What would it mean for her to act as a good citizen in this situation? In turning to discussing and debating the dilemma, we often suggest that individuals turn to respected others—mentors—in order to ask for their advice. Importantly, a mentor might not always be a single person to whom one looks up; rather, that mentoring role might be assumed by a fictional character, or individuals might pull different lessons from several individuals, a process we’ve referred to as “frag-mentoring.” At The Good Project, we also speak of the importance of “anti-mentors”—looking to examples of who we don’t want to be in a situation. Thus, in this situation, Sara might ask mentors in her life what they would do in a similar situation in order to be respectful to both family and work responsibilities, or, instead, what they did if they ever encountered a similar experience. (And if the mentors were not available, she might try in her imagination to recreate the advice that they might have given.)

In debating the possible courses of action, Sara should also refer to the Rings of Responsibility—whom will each course of action serve? To whom will she be acting responsibly if she crosses the picket line? What about if she elects to skip the WEF meeting altogether? Which action allows her to better serve her communities in an ethical, engaged, and excellent manner? For example, Sara might consider that:

By attending, she might help her national nonprofit; she also could be furthering the needs of the communities that her nonprofit serves; she would be upholding her ethics of as a social entrepreneur; and she would be fulfilling a responsibility to wider society by serving an underrepresented workforce.

By not attending, she might serve her image of herself as a supporter of workers as she honors the picket line; she could be serving her family by upholding her grandfather’s union legacy; or she might be serving her community (and the broader society) if she is publicly displays her support of others in the labor movement.

In wrestling with this dilemma, Sara would also need to consider her own values and how they might affect her decision regarding this dilemma. Perhaps she is already aware of her own values; or perhaps she might conduct an inventory, by taking a survey such as The Good Project’s Value Sort. Which course of action would be more aligned with Sara’s own values? We often speak about alignment as something that occurs when various groups or parties want the same thing or are working towards a common goal; but this desired balance can also occur within an individual when someone’s thoughts, actions, and values align with one another.

Deciding on a Course of Action

Which course of action should Sara take? As we’ve described it, a “good citizen” is someone who acts in accordance with all three “Es” —specifically taking into account the community or communities to which that person belongs. Again, she might consider:

Ethics: Sara has acted ethically if she makes a decision in light of her responsibilities to her several communities (to her organization, to the unions, to the ideals represented by the freedom to demonstrate), and if she acts in a manner that she believes will ultimately do the most good.

Excellence: Sara knows the norms and rules of her various communities well and in fact, her desire to adhere to the norms of one of those communities (i.e., not to cross a picket line) was what brought about her quandary. She recognizes that if she does an excellent job at the event, the potential impact she might have will expand her connections within the political community.

Engagement: Sara has been deeply engaged in her work. Because this event brought together multiple communities of which she considered herself a part, the issues were especially relevant. She also is engaged with her family and does not take that affiliation lightly.

Debriefing

When posing such a dilemma to students, we typically do not reveal an answer—it’s the process of applying the 5 Ds that is crucial.

However, here we can reveal that Sara elected to cross the picket line. She concluded that the harm her action might cause would ultimately be outweighed by the good she might be able to achieve by attending the event, making contacts, speaking on behalf of her beliefs about labor, and ultimately, furthering her cause. She acted in accordance with what she felt might, eventually, do the most good. In some ways, she chose long term over short term gain. Upon reflection, Sara was not fully at peace with her decision (she said she could never feel fully at ease crossing a picket line), but she felt that she made the best choice she could have at the time.

As mentioned above, there may at times be overlap between “good work” and “good citizenship.” In this particular case, Sara understands herself to be responsible to multiple communities and does her best to take these communities into account in her decision-making. The good work of a nonprofit director requires Sara to be a good citizen.

Debriefing also involves a consideration of longer term consequences. Did Sara’s decision cause any family estrangement? What did she accomplish at the event, and were these accomplishments worth crossing the picket line? Would she make a different decision in the future, and why? These are the types of questions to consider in our efforts to foster good work and good citizenship.