by Danny Mucinskas

The Global Education & Leadership Foundation (tGELF) is a not-for-profit organization that seeks to foster young leaders from around the world with strong ethical and altruistic values to face the challenges of tomorrow in a network of schools in India and 13 other countries. Over the past several years, the Good Project and tGELF have partnered in an effort to incorporate Good Work ideas and practices into schools and teacher development.

In April 2015, we spoke with Dinu Raheja, Program Director, about recent events at tGELF, including how Good Work continues to be present in school communities, the rationale behind a new prize for teachers, and how tGELF is fostering the next generation of trailblazers.

Q: What motivated tGELF to create The Education Prize 2015 (an award for teachers who have made an innovative contribution to improve practice and inspire students)?

Dinu: We believe that the best way to impact student learning on a daily basis is to honor how teachers teach. Our goal with the instatement of The Education Prize is to recognize an educator who excites learning and a hunger for knowledge in his or her students. We want to find the next Socrates: someone who is able to connect with students and who uses innovative techniques to create new methodologies that can improve the educational landscape.

Q: Were there any connections to Good Work themes in the development of the prize?

Dinu: There may not have been overt connections, but unconsciously or subconsciously, there are definitely connections to the Good Project. tGELF has exposed students and teachers to ideas from the Good Project, and in the back of our minds, in whatever projects we undertake, our philosophy is to forge a better world by taking steps in a positive direction. We want to reward the Good Work that happens in our world, and in doing so, we are trying to do Good Work ourselves.

Q: What are the biggest challenges facing teachers who would like to do Good Work?

Dinu: In a sense, there are no substantial challenges if you are focused as a teacher in your vision of doing Good Work and imparting that ideal to students by ensuring that they do the best that they can. It is important to constantly encourage students to do better over time. A teacher can become accustomed to thinking about education in this way.

On the other hand, if an educator is constantly raising the bar, that is a challenge in itself. By raising the bar too high, it may end up demotivating the teacher and/or the students. There is a risk in always striving for improvement because you can forget how to have a more tolerant understanding of expectations and therefore not achieve all that you hope. Yet another challenge can occur when the difficulties posed by teaching and Good Work cause an educator to become depressed and capitulate.

Therefore, whereas there may not be challenges for particular teachers, there may be several challenges in place for others attempting to do Good Work. A lot depends on the attitude with which a teacher comes to the task at hand, asking “Am I willing to accept challenges and not regard them as challenges, or am I going to get bogged down by them and end by giving up?”

Q: How or in what ways is Good Work integrated into the tGELF school network?

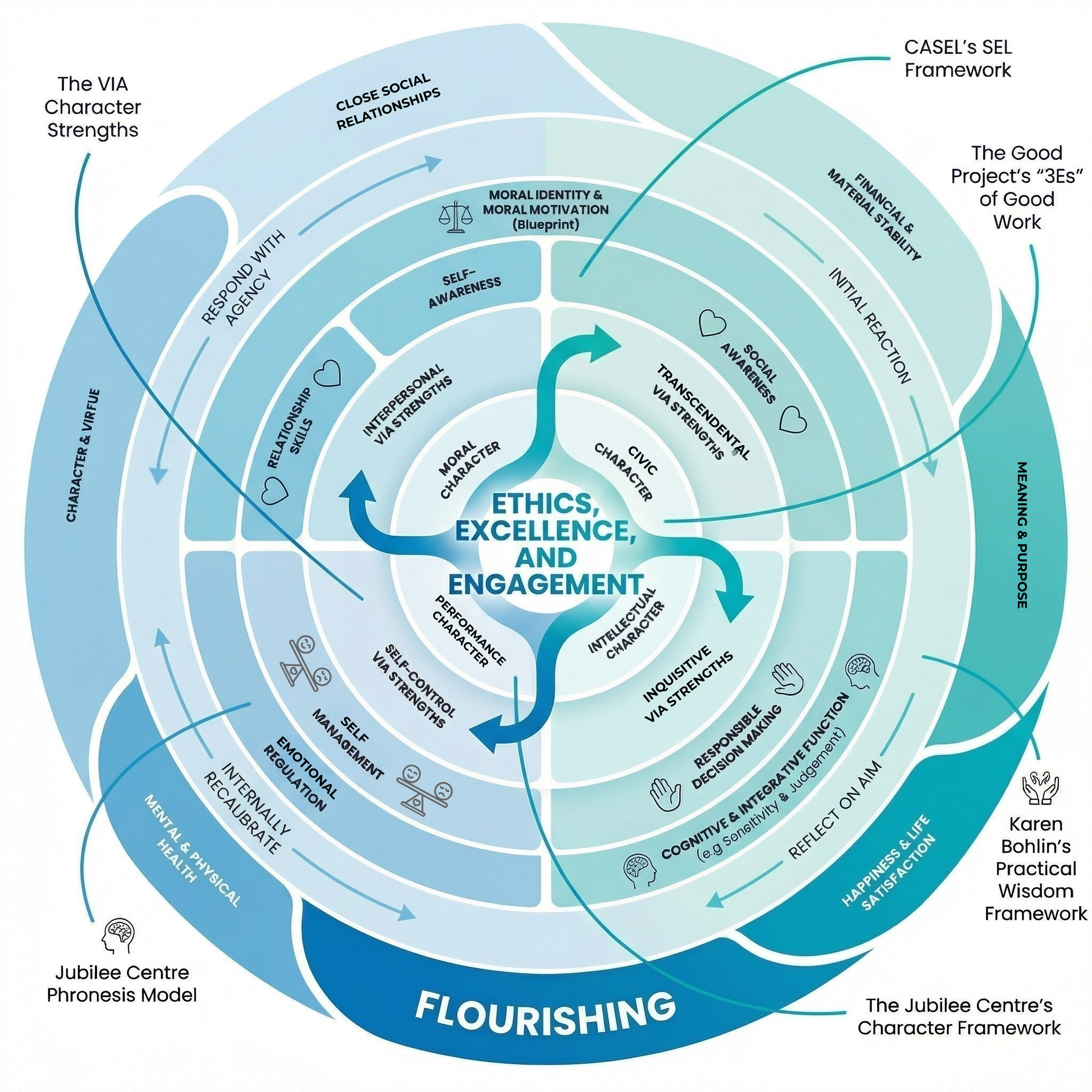

Dinu: When we talk about leadership at our schools in our leadership curricula, we discuss the Good Work Project’s 3 Es: Excellence, Ethics, and Engagement. Leadership means excellence in what you do, and in tGELF’s own philosophy, we try to foster value-based, ethical leadership. Furthermore, there can never be leadership in isolation, so by extension, being a leader necessarily involves teamwork and engagement with others. I think our two organizations interconnect on a lot of frameworks, including that of the meaning of leadership.

Q: What changes or observations have you noted in schools using Good Work?

Dinu: We have seen a positive change in how teachers work in schools and in the attitudes of students towards their work. We believe there has been an attitudinal shift due to the introduction of Good Work ideas in our school communities.

Q: You mentioned that you are working on a leadership program that will integrate the 3 Es of Good Work (Excellence, Ethics, and Engagement) into a curriculum for students. Where are you in this process?

Dinu: We are currently holding training sessions with teachers to prepare them to use the leadership curriculum in their classrooms. Depending on the number of participants, this is either a 1 or 2 day training process in which teachers are completely familiarized with the philosophy, objectives, and learning outcomes of our leadership curriculum. The teachers then deliver the modules directly to their students. We have found that teachers really look forward to and enjoy the training workshops, and we hope that they then convey this enthusiasm to the students.

The curriculum is age-appropriate and is used from grades 6-12, consisting of activity-based 35-40 minute lessons. We are also considering eventually bringing the modules to the primary level. We view the program on leadership as intertwined with the academic curriculum in these schools; it is not something that we consider separate.

Q: Are there any other updates from tGELF that you would like to share?

Dinu: Right now, tGELF is getting ready for “Harmony,” our annual youth festival. This is an international school-level series of events in which we bring students and teachers together on a common platform in a series of competitions.

For example, we facilitate a six-month youth leader competition that recognizes and initiates volunteerism. Students in this competition design specific service projects in their communities in order to tackle a problem or concern. Once a project design is accepted by our judges, students implement their plan and put their leadership training into practice, reporting back to us with the results. (One recent outstanding student project involved the construction of over 70 toilets in a rural area of India without regular public bathroom access.) Finalists are invited to make presentations about their projects at the “Harmony” National Final Event in November. The Final includes Leaders Club members and winners drawn from a spate of other competitions that are held at the regional level throughout our network. Last year, we hosted about 500 children from three countries, allowing attendees to make connections with one another and further develop their leadership skills.

Finally, in August every year, we organize a residential conference called LIFE (Leadership Initiative For Excellence) for our Leaders Forum members. Leaders Forum members are undergraduates, graduate students, or young professionals selected through a rigorous admissions process based on our four pillars of Leadership, Ethics, Altruism, and Action. The purpose of the program is to mentor and guide young people to make ethical choices in their chosen career paths. In a typical year, tGELF welcomes about 300 people from all over the world to the LIFE conference. This year, we will also be holding a LIFE-USA conference in September in New York City.

More information about tGELF’s programs is available on our website at www.tgelf.org.