by Wiljan Hendrikx & Hans Wilmink

What does the craftsmanship of Dutch civil servants entail, and what does it take to support it?

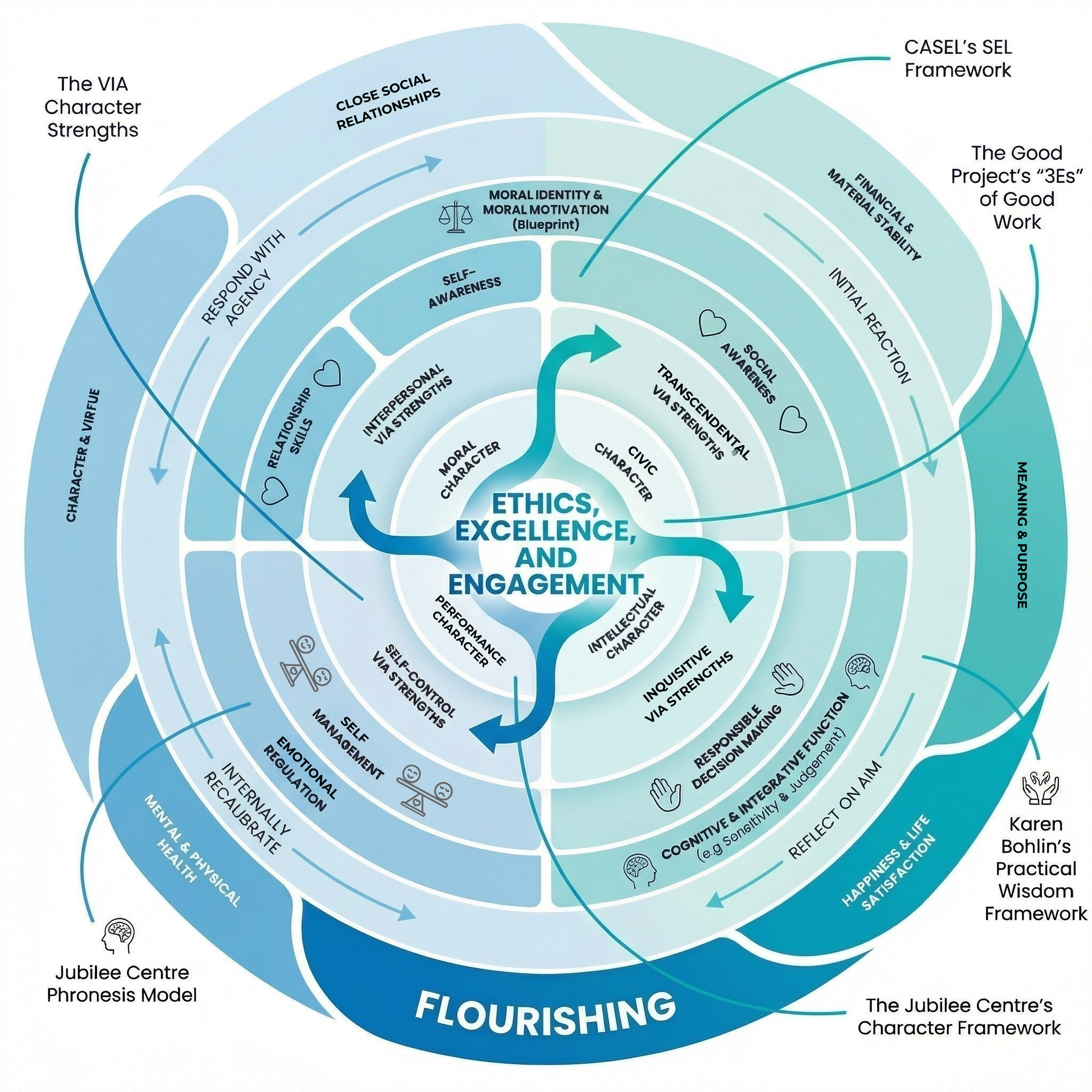

Faced with this challenging question, a Dutch Ministry’s HR department in The Hague called the Dutch Professional Honor Foundation for help. Armed with a Good Work Toolkit-based approach, 4 groups with a total of 28 participating civil servants took up this challenge with their peers in 4 sessions per group. The 16 meetings were organized between October 2013 and January 2014. Together they formed a ‘developmental trajectory’ aimed at exploring civil servants’ Excellence, Ethics and Engagement, and strengthening their capacity to recognize, think about, discuss and act upon dilemmas faced in daily working life.

In 2 of the 4 groups there was debate about the approach used at the start of their first session. Participants were uncertain about what to make of the project, and their questions centered in particular around the intentions of the ministry:

“To explore and define for yourself what the core of your role entails? Is this really what the ministry expects us to do? Do we really get the discretion to think about these issues and discuss them independently?” they questioned. Moreover, a tone of uncertainty also resonated through their questions; civil servants had to ask themselves: are we capable and reliable workers or are we independent professionals?

Despite these initial doubts and hesitations, practically all participants pushed through. During the project, the tide turned and participants started to actively engage in the debates about Excellence, Ethics and Engagement within their own work, eagerly sharing their own stories. By the end of the project, a delegation of participants even volunteered to exchange thoughts with the ministry’s management on how to continue working with Good Work ideas and notions.

We can report several interesting findings based on the group discussions. First of all, we came across a number of core motives that civil servants – at least of this particular department – seem to share, causing them to be really engaged with civil service. First, our participants shared a strong desire to serve their minister, regardless of his/her ‘political color’. “Serving your minister” was seen as an honorable duty in and of itself. Second, they expressed a strong wish to put their expertise to (good) use. Being able to show what you can do and being appreciated for doing so within as well as outside of the organization is rewarding. Values like” being objective” and “independence” were often mentioned in this context – having the discretion to think for yourself independently of dominant trends. Third, our participants all felt personally involved in the policy domain of their ministry and the ‘common good’ it strives to serve.

Moreover, the group sessions allowed us to identify several dilemmas and tensions civil servants encounter in their work. First, there is a strong tension – sometimes even conflict – between civil service and political management. The bifurcated point of view of a professional civil servant and of a member of a political party often lead to vastly different solutions to a problem or situation; the latter attaching much more value to political feasibility and desirability. Second, we can discern a tension between civil service and society. A problem orsituation can be perceived in a completely different way from a technical/professional viewpoint than from a societal one, creating imbalances in the societal support base. A final tension we came across is between political management and society. Not only politicians, but also civil servants need to have a keen eye for societal interests and sensitivities. It is not directly up to the civil servant to neutralize the tension, but it is seen as his duty to signal and explicate these in order to communicate them to their political management, even when they are politically unwelcome.

Using Good Work concepts of Excellence, Ethics and Engagement to explore and discuss civil servants’ craftsmanship really opened discussions that would not have otherwise been possible. A narrative-based approach combined with small discussion exercises turned out to be a good starting point for debate. The greatest challenge for our participants was the use of the Good Work Toolkit’s narratives. Despite the undisputed quality of these stories, the civil servants did not recognize themselves enough in these stories, nor did they associate them with their own experiences. Our important lesson: focus on narratives from the profession itself right away and use these to collect participants’ own – similar – stories as soon as possible. As a consequence, we have developed our own toolkit, particularly aimed at civil servants (see Gerard van Nunen’s blog).

During a final collective session, after the end of the project, 14 participants volunteered to assist the ministry in its efforts to make Good Work for civil servants commonplace. This is an initial, promising sign that we have had some impact. We look forward to maintaining and improving civil servants’ craftsmanship through regular discussion and reflection among peers, based on our shared narratives.