by Danny Mucinskas, The Good Project researcher

City of Boston

The COVID-19 pandemic sweeping the globe has had detrimental effects on many aspects of modern society. The primary concern is naturally the toll that the virus is having on human life and national healthcare systems, which many governments have attempted to ameliorate by enacting unprecedented lockdown measures and social distancing guidelines.

In addition, the crisis has also been wreaking havoc on the economy: stock markets have become volatile, businesses have lost revenue, and unemployment claims have hit record highs. The financial instability has caused many people to face dilemmas related to doing excellent, ethical, and engaging work at a time of intense stress. For example, employers have had to lay off valued and loyal employees; essential workers daily weigh the risks to their health as they report to their jobs; and vast numbers of people are now figuring out how to deliver services online that were formerly conducted in-person. Needless to say, these are challenging times for doing “good work.”

In the Boston area, small businesses have been especially hard hit by the loss of customer revenue as Massachusetts has been in a state of quarantine for a month. The Boston Globe reports on April 8 that a group of vendors with leases in the landmark Faneuil Hall marketplace has appealed to the real estate company that acts as its landlord for an extension on their rent payments. Despite the circumstances, the landlord has responded that the tenants are still required to pay their rents on time and should take advantage of government programs if they are unable to do so on their own.

What does it mean to do “good work” in this situation, for both the tenants and the landlord? How can both sides uphold their responsibilities to one another, in formal and informal ways?

In “normal” times, the formal working relationship between tenant and landlord comes along with responsibilities that fall under the umbrella of The Good Project’s concept of the “ethics of roles.” Those in the role of tenants are expected to pay their rents on time and fulfill the terms and conditions of their leases. On the other hand, landlords normally fulfill their role by collecting rent, holding tenants accountable, and maintaining their properties accordingly.

However, as American society faces the first true pandemic in a century, tenants and landlords may have to recalibrate their formal contracts with one another for a period, as others in different working roles have already done. For example, medical professionals who would normally require patients to visit their offices have begun conducting remote appointments; retail operations have instituted new rules about store capacity and hours; and companies like Amazon that pride themselves on fast delivery have prioritized the shipping of crucial materials, resulting in delays on other orders. Despite the set of assumptions under which we usually operate in our work, sometimes adjustments are advisable or necessary, given mass events beyond anyone’s control.

In the case of Faneuil Hall, the tenants, most of whom are small business owners, are not currently able to fulfill their leases by paying rent on time, given the downturn in customers. Yet they have not simply defaulted or refused to pay but instead appealed for a reprieve, asking for the real estate company to temporarily adjust expectations for the period of the crisis.

Unfortunately, the real estate company’s representatives have demonstrated that they are not at all thinking differently about their relations with tenants during this time, expecting the literal terms of their agreements to be respected as they would be during “normal” times. The landlord effectively rejected the tenants’ requests. How can the disconnect be bridged?

One way to broaden perspectives is to think not just about what landlords and tenants should expect of one another during normal times to satisfy their respective “ethics of roles” but also to consider what it means to be a “good citizen” of a community and show “neighborly morality” to others (think of the Golden Rule as one example).

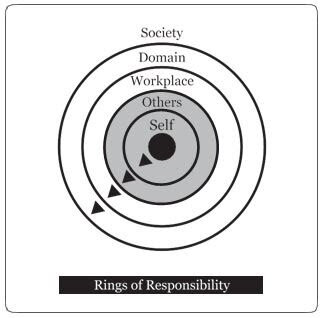

The Good Project’s rings of responsibility are one tool to guide decision-making in tricky situations. As the rings show, wider responsibility means not only prioritizing oneself, a contract (such as a lease agreement), or one’s institution (such as a real estate company), but ultimately entails a responsibility to the communities and societies in which one participates.

Given the wider lens, my belief is that the real estate company should not just seek to act in the normal role of landlord, given the disruptions that COVID-19 has wrought on the economy. A better way to approach the dispute would be to demonstrate a responsibility to the tenants as mutual members of a business community and as fellow “good citizens” of the city and country.

For example, the real estate company’s representatives could at least come to the table with more information about why a rent extension is impossible (perhaps they are in dire financial straits themselves or would not be able to carry out other responsibilities to other properties without the income). Instead of outright rejecting the tenants’ proposal, the landlord could have also proposed another solution to assist tenants with their leases.

“Good work” can still be carried out in the era of COVID-19 and in other challenging circumstances in the future, but it requires openness, honesty, and a commitment to making choices that take into account long-term social and community benefits, not just short-term gains or consequences. I hope that the landlord will ultimately make decisions that uphold both “good work” and demonstrate a responsibility and understanding of the circumstances of others, which may help ease the return to “normal” and “business as usual” for all of us.