by Kirsten McHugh

Typically, parents and teachers have complementary roles, and can function in relative independence from one another. This has not been a typical year. In 2020, except in places where children are physically back at school full-time, parents (whether they felt they signed up for the task or not) have had a new assignment thrust upon them--that of teacher. For many, in addition to being “good parents”, and/or “good workers”, parents are now figuring out how they can also be “good teachers” to their children. There is now a lot of serious discussion among parents who are understandably overwhelmed by this proposition.

The average parent has little to no experience being in a teaching position—save for the chaotic few months last spring when the entire educational system was abruptly thrust into remote learning. At the time, most jurisdictions were forced to use clunky but readily accessible educational platforms implemented as a stop-gap at the start of the pandemic.

The summer break has provided school systems with a chance to integrate their curricula with more specialized online learning software. Teachers have explored new tools to assist in their technological pedagogy while simultaneously transferring in-person teaching materials into digital formats. There has been a lot of debate over whether and how schools will reopen and if so, whether or not parents will send their children in or keep them home (that is, if this is a decision they have the luxury of making). There has been far less discussion about how to support parents as they prepare for the fall: circumstances have given them a new role within the educational system, but are parents able to take it on? Should they?

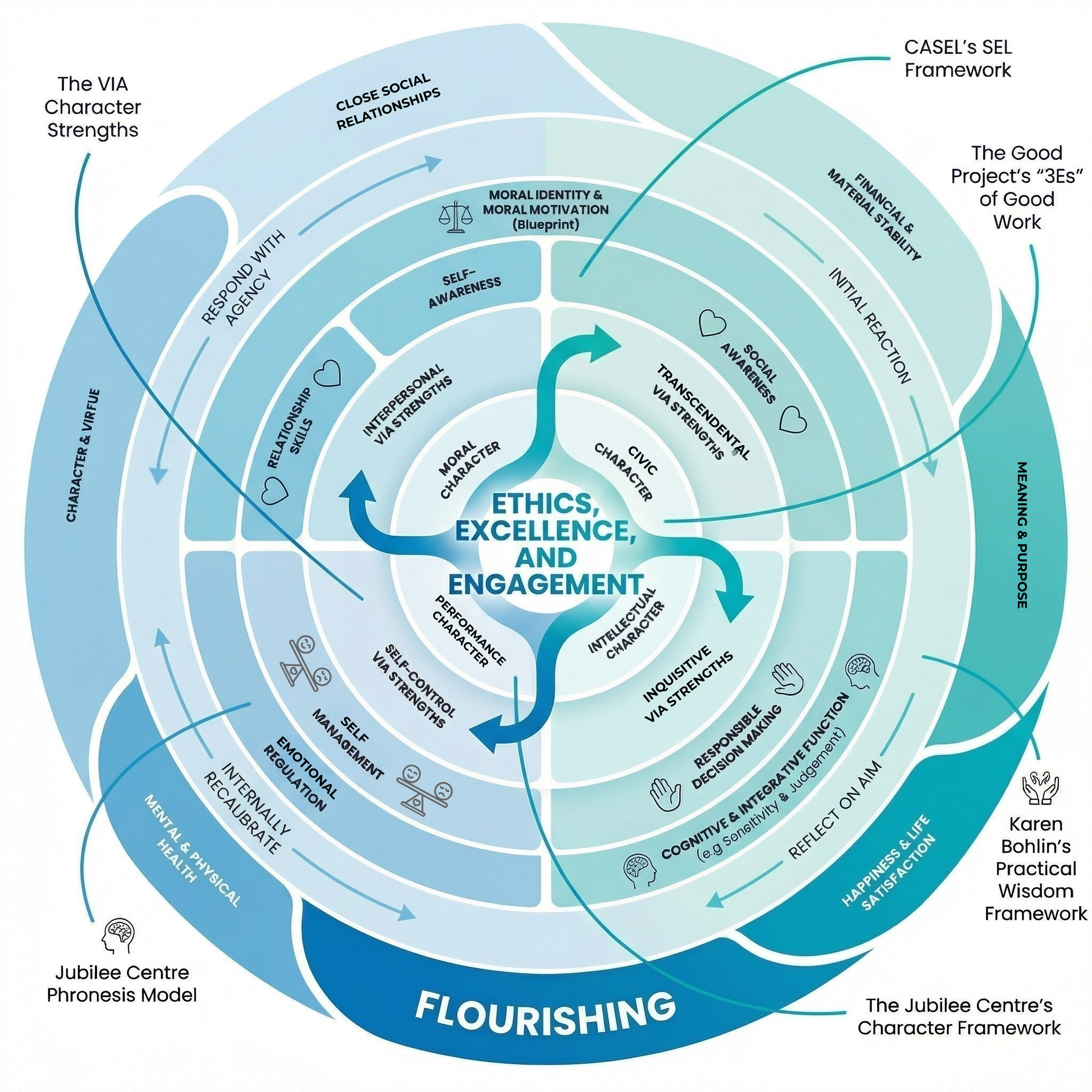

We here at The Good Project are not experts in how to balance all of the competing demands on parents, but we hope that our tools and ideas can provide some ways for parents to think about how they plan to approach the situation. As an example, parents might consider approaching the situation through the lens of the 3 E’s of Good Work: excellence, ethics, and engagement.

Engagement

Engagement might be the most challenging of the 3 E’s for parents to embody in their support of remote learning during the current crisis. This is a stressful time for each and everyone one of us. The pandemic and the upheaval of our regular lives has been jarring. This stress is a direct obstacle to engagement.

The scenarios parents now face are wide-ranging. For one, the age of the children plays a huge role in parents’ experiences during this time. Parents of young children, such as myself, are trying to keep little ones engaged and entertained, those of older children are trying to find ways to balance staying involved without hovering. Parents of college-aged students have their own set of issues. Many want to treat their “children” as the adults they are but are torn about what the “right” thing to do is in such unprecedented times.

Another consideration is whether or not one or both parents are working and if so, whether that work is full-time, part-time, in the home or outside of the home. Some parents are still able to access childcare and/or in-person schooling (at least at this point), while others are not so fortunate.

I have a toddler and a preschooler at home. This year our preschool chose to remain closed, and childcare is unavailable. We will attempt to work on pre-K skills with my oldest, while desperately trying to keep our youngest from her favorite activities of mayhem and destruction. My husband works full-time outside the home, and I fit remote working hours into mornings, evenings, nap-time, and (mostly) weekends. One other team member has an elementary school aged child who is learning remotely at home. With both parents working full-time jobs also remotely, there is frustratingly little time to fully engage as “assistant teachers.” Another team member has college-aged “children.” She has described an entirely distinct set of issues around learning to let go in order to allow these young adults to make their own decisions in how they approach their schooling this year. Her family has had multiple conversations about sharing and balancing household tasks (cleaning, laundry, preparing meals, walking the dog) as well as negotiating tight space for 4 separate but often simultaneous Zoom meetings. We also have a grandfather on the team who is working on “higher education capital“ with his high school age grandson, while his wife (grandma) is working on the 3Rs with her younger granddaughters. They hope to aid in relieving parents and cementing generational bonds.Parents who work in “essential” roles often don’t have the luxury of being physically present. Some parents who are unable to stay home must ask older siblings and family members to watch over their youngest children. These examples are but the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the range of experiences for parents at this time.

How can each of us be “engaged” as parent-teachers while also staying “engaged” with our work? The unfortunate truth is that we can’t be fully engaged in each role at once. One thing we can try to do is be as present and positive as possible when we are able to turn our attention to supporting children’s school work. This is admittedly a tall order, and it won’t always be attainable. Think of it as how you would like to play out the role of parent-teacher on your best day, but know that there will be highs and lows. I can admit as a parent that we will all certainly be exhausted and stressed while working through the coming months. However, when we can muster it, we should try to be positive in our support of children’s learning.

I am personally trying to think of this E as a quality over quantity. If parents are engaged when available and can make that engagement visible, manifest, the learning may be contagious. We all remember the teachers who inspired us and those who seemed less than enthusiastic about their subject matter. Which approach motivated you to apply yourself?

Parents might also check in with children (or the whole family) to make sure they are aligned in their understanding of what is “engaging”. It's important for the parent to adapt their ideas to what the child needs in order to spark interest and engagement (parent-child fit) particularly for young children, and to focus on things that are relevant to their lives for older teenagers.

Finding ways to involve children’s peers will be important (though admittedly difficult to do) at a time of social distancing. As one example, parents may consider socially distanced nature walks or outdoor discussions when the weather permits. Gamification has a huge pedagogical following; many online resources incorporate this type of interactive play as a means of increasing engagement in learning. Our own research hub, Project Zero, has curated a set of resources and tools for remote learning applicable to a range of subjects and grade levels.

Excellence

Excellence in good work terms means to set the bar high and aim to master the field or role. For all the reasons previously discussed, most parents cannot expect to become masters of subject matter or pedagogy. Luckily, many parents have gone through the same grades and subject matter as their children. That being said, as time has passed, that knowledge is presumably eroded, and new information of all sorts has also likely emerged.

Fortunately, this isn’t 1918. We have a wealth of information readily (and often freely) available. In person research at libraries may be off limits at the moment, but sites like Khan Academy, Coursera, and edX offer a slew of classes for little to no cost. If students are struggling with a particular topic, it is possible to supplement learning in short-time and without expending additional financial resources.

This could also be a great time to sub-in grandparents or other available close trusted friends or relatives over Zoom or Facetime. It seems that spare time is either a feast or famine for those who are quarantining at home. If you know someone who is feeling a little stir crazy and looks like they could use a little break from nurturing their sourdough starter, see if they might be game for playing remote tutor from time-to-time. It may be a win-win for at least an hour!

Good teachers don’t just know their subject, they also know how to effectively translate the information to their students. To be sure, parents won’t become master teachers overnight but, if they have the bandwidth, they can learn enough to at least consider themselves “apprentice teachers.” Again, there are amazing resources available online (some for-profit, while others are free). Another approach parents may consider is to speak with their children’s current and previous teachers to get a sense of what the strategies will be this year, and what has worked well for their child in the past.

These are just a few examples that we hope can help parents to feel more confident and prepared. That being said, what parents can and cannot take on is entirely relative. Parents need to be flexible and patient with themselves as they navigate the school year.

Ethics

As a society, we haven’t really had a chance to fully consider the ethics involved as parents help support student learning at home. Surely, parents will need to model ethical standards with their children while they precariously balance the twin roles of nurturer and educator. Children look to parents while developing their own moral compasses and this intensive time of parenting and teaching will expose both the good and the bad. As an example, both online and in-person learning is subject to cheating. Now it will be up to parents along with teachers to ensure that children learn the importance of academic honesty in their work.

Parents who have the means to hire tutors or join in private learning pods might reflect on their privileged position in society. Educational inequity has been a long-standing problem in our country and the pandemic is unfortunately exacerbating the issue. One way of modeling ethical behavior is to consider underwriting those who are less financially secure. This could take the form of donations to local schools for those less privileged; encouraging fellow learning pod members to sponsor the inclusion of a dedicated student who lacks the necessary resources; or contributing to funding towards childcare for essential workers. Many of these essential worker-parents may not be able to afford the expenditures tied to creating a fully functional remote learning environment; but it’s their work that keeps the rest of our society running. There are many obstacles to learning during a pandemic and these are just a handful of ideas of ways that you might consider your responsibility to those outside of your immediate social circle.

Again, these are just a few examples of how parents might take ethics into account. New scenarios and dilemmas will likely present themselves over the course of the year and with them creative ways to “do the right thing” will also emerge.

Whether you are a parent, a teacher, neither, or both, what do you think? Do you have any additional idea of ways you plan to embody the 3 Es? Which do you expect to be the most challenging for your family?

Check out our Value Sort tool to help you think through how your own values might relate to the questions of the 3Es and how you might approach a new role in your own life.